Your friendly neighborhood Spider-Man could be a little bit friendlier

Peter Parker learns that with great power comes great…pain, along with various cuts, bumps, bruises, strains, sprains, and the occasional broken bone and odd scratch. What it doesn’t come with is a great deal of fun, at least not in The Amazing Spider-Man, starring Andrew Garfield as Peter and now out on DVD.

Didn't write a formal review when we saw The Amazing Spider-Man in the theater back in July, but I posted a few thoughts, Spidey Thoughts, and in Spidey Thought Number 4 I noted that the movie begins with Andrew Garfield’s Peter Parker already Spider-Man in every important way except for the minor detail of not having spider powers.

He's brave, he's cocky, he's a wiseguy, he's a genius scientist---this is very important because, as I noted in Spidey Thought Number 3, most of his major enemies are mad scientists and/or victims of science experiments gone tragically awry---he's a natural born detective, and he's a hero. Heroic, at at any rate. This Peter Parker is only a target for bullies when he deliberately gets between the bullies and their first targets. He stands up for---and gets knocked down for---the weak against the strong.

It's not the case with Peter as it is for Steve Rogers in Captain America: The First Avenger that his powers are the expression of his innate goodness and strength of heart. For one thing, Peter’s spider powers appear as temptations. Rogers goes right to work at being Captain America. In The Amazing Spider-Man, Peter starts off in a less than heroic direction. But like Rogers, he doesn't need superpowers to be a hero. Only to become a super-hero.

What this means is that, essentially, at first, there is no Spider-Man. There is only Peter Parker wearing a disguise he calls Spider-Man.

His challenge is to make Spider-Man into something more and greater than an alter-ego: his job and his vocation. He has to turn that disguise into the uniform of his new chosen profession. Your Friendly Neighborhood Spider-Man.

This is a key point, thematically, as far as it goes, which turns out to be not far enough.

The first Tobey Maguire Spider-Man was about Peter learning how to be Spider-Man. The Amazing Spider-Man (the first half of the movie, at least) is about Andrew Garfield’s Peter learning to be Spider-Man and what it means to be Spider-Man.

As I mentioned, Peter is not in a heroic frame of mind, nor a particularly friendly one, when he starts webslinging. He’s not in the mood to use his powers for good and not for evil. He’s in the mood to use them for revenge.

He’s out to get the thug who murdered his Uncle Ben. Any crooks he captures along the way are---what’s the opposite of collateral damage? Collateral success?

He’s not even the vigilante Captain Stacey calls him. Vigilantes are at least nominally interested in justice. Peter is only interested in assuaging his own emotional pain. He’s using his powers to work out his guilt. What he has to learn is that he didn’t fail by not stopping the robbery that led to Uncle Ben’s getting killed. He failed by not doing the right thing for the simple sake of doing the right thing.

He has to learn that he has an obligation to help people, because with great power…

But he has to learn something else. This.

He has to learn that being Spider-Man is fun!

You’d think there’d be joy and a thrill in being a superhero who has the proportional strength of spider, can climb walls, spin webs any size, and catch thieves just like flies. And it should feel good to have the power to do good and then go out and do it.

Plus, it’d be really cool.

Peter learns this. Or he says he does. He has an epiphany after his first fight with the Lizard---in a scene on a bridge unfortunately reminiscent of the much better staged and much more suspenseful bridge scene in Maguire’s first Spider-Man. “Who are you?” asks the father of the little boy he’s just saved, his first truly good deed as Spider-Man, the deed that in fact makes him Spider-Man. And that’s his answer. “I’m Spider-Man.”

He should say something else. The guy knows he’s talking to Spider-Man. J. Jonah Jameson (not seen in this movie because the producers had the good sense to know it’s too soon to ask any actor to try to follow J.K. Simmons in the part, but he makes his presence felt) has already been at work making sure the whole city knows he’s Spider-Man. What Peter should say is “I’m your friendly neighborhood Spider-Man” which would be a way of claiming the name Spider-Man for himself and announcing what his job is now. He’s a public servant. Every neighborhood has one, right? Along with the cop on the beat, the letter carrier delivering the mail, the firefighters in the station down the block? And he ought to say it with delight and with a great big grin that we should sense through his mask. And then we should see him go off and have some fun in a series of scenes like the ones that make up Superman’s first night in the Christopher Reeve’s first Superman, capturing jewel thieves and bank robbers for the pure, unselfish rightness of it.

It doesn’t happen.

Instead he swings over to his girlfriend Gwen’s apartment to tell her in the mopish way she inexplicably finds endearing that that’s what he’s going to do from here on out.

Which is a letdown, as endearing as it is to watch Emma Stone acting as if Garfield’s moping is endearing, but it would be something to shrug off if the movie had let him to follow through on his promise.

He doesn’t get the chance. He has to go back to being plain old Peter Parker on a personal mission. The Lizard’s on the loose and it’s his---Peter’s not Spidey’s---responsibility to stop him.

When asked why it’s his responsibility, Peter replies, “I created him,” making it all about him and between him and the Lizard.

Spider-Man isn’t really part of it and goes back to being the name for the disguise Peter doesn’t really need at this point.

Never mind the stampeding crowds, exploding cars, and massive destruction of private and public property that has become the signature of too many Marvel Comics-based movies---both Iron Man movies, both Fantastic Four movies, Spider-Man 3, The Incredible Hulk, and The Avengers all end with the same insurance agent’s nightmare in the city streets---the final battle in The Amazing Spider-Man isn’t a fight to save New York City. It’s a struggle to save Curt Connors from himself. Spider-Man can’t do it. But Peter Parker can…by using SCIENCE! Spider-Man is just there as a distraction to keep the Lizard away from the Oscorp lab while Gwen concocts the serum that will cure Connors based on a formula devised by Peter.

In the end, The Amazing Spider-Man turns out to be a personal drama about a philosophical disagreement between two scientists.

Another way Connors is interesting is as Peter’s nightmare of himself as monster come to life. Connors is Peter’s double. By virtue of his scientific genius, Connor has great power but he’s always in danger of forgetting the responsibility that comes with it. The movie could have made that a subplot, with Peter coming to realize how he and Connors are alike and that he faces the same temptation to use his powers if not for evil then for personal satisfaction and not for the public good. They’re also alike in that as both freaks and geeks they’re outsiders and misfits who can only fit in by not being themselves.

It’s understandable that outsiders and misfits of all sorts dream of a world where the definition of “normal” and the rules that decide popularity are expansive enough to include them. The intellectual temptation, though, is to insist that “normal” and “popular” ought to be redefined to mean them and it’s up to everybody else to conform. In real life, giving in to this temptation is usually only self-destructive because it leads to anger, resentment, bitterness, and further alienation and isolation. But Connors has the power to make others conform to his idea of “normal.” And that’s the motivation director Marc Webb and and his team of screenwriters have given him.

This is an apt theme for a movie based on a comic book that became famous for having a teenage hero who had to deal with the typical problems of an ordinary high school kid while saving the City from the likes of the Green Goblin and Doctor Octopus. Almost every teenager, even some of the popular ones, feels as freaky and geeky as Peter Parker at some point. One of the things I liked about this movie (and it probably sounds as though I didn’t like much. I’ll deal with that in a minute.) is that it lets us see that the popular jock Flash Thompson, Peter’s high school nemesis but future good friend, feels like an outsider and a misfit.

But it turns out the movie isn’t really interested in that theme. Connor’s crackpot scheme for world domination is just an excuse for the preview of the video game that’s the final confrontation between cgi Spidey and the cgi Lizard.

So, here’s the progress of Peter Parker through the three acts of The Amazing Spider-Man:

I. Peter Parker, budding boy hero but ordinary mortal, struggling with his sense of identity.

II. Peter Parker, spider-powered angel of vengeance, using his new abilities selfishly.

III. Peter Parker, super-scientist.

Peter Parker, the actually amazing Spider-Man? Pretty much offstage throughout.

Now, onto what I liked.

The cast.

I enjoyed The Amazing Spider-Man more than I thought I would when we saw it in the theater. I enjoyed it even more watching it again on DVD. It's not as good a movie as either of the first two Maguires. (I think we all can agree to pretend Spider-Man 3 never happened.) But it's different enough to have earned the right to be judged on its own merits. And one of the very good ways it's different is in having a heroine who is not just a damsel in distress.

Kirsten Dunst’s Mary Jane Watson spent a lot of time in all three of her Spider-Man movies literally hanging around screaming for Spider-Man to come to her rescue. When she wasn’t doing that, she didn’t seem to have much else to occupy her time except fretting over her relationship with Peter.

Emma Stone’s Gwen Stacy is never in distress. The script doesn’t put her in need of rescuing at any point, but if it had, we’d know she’d figure her own way out of her fix without wasting time screaming for Spider-Man to come save her.

This isn’t naiveté. It’s insight. It’s how she handles her demanding and irascible father. She’s not defiant. She’s not rebellious. She just won’t to talk to him as if there’s any other side to him except the loving, considerate, and understanding side. And she won’t let Peter keep secrets. He has to confess to her he’s Spider-Man because she already knows he is---that is, she knows he’s a hero and won’t talk to him as if he’s not. I wish the director had given her a scene with Connors in which she did this with him. It would have been heartbreaking to watch both of them realize that that side of him she admires is on its way to being lost.

As Gwen's irascible father, police Captain George Stacy, Denis Leary is as convincingly upright, noble, reliable, professional, public-spirited, and incorruptible as he is convincingly all the opposites as Tommy Gavin in Rescue Me. Stacy is always stern and earnest, but Leary gives him an underlying sense of humor and sense of proportion to make us believe that despite his present antipathy he is the character we know from the comic books (the originals not the Ultimates) will eventually get and appreciate what Spider-Man is about. It's too bad the next movie won't be bringing Leary and J.K. Simmons together so we can have the fun of watching Stacy and J. Jonah Jameson go at it over the Bugle's treatment of Spider-Man.

Rhys Ifans plays Curt Connors as a self-absorbed but basically high-minded scientist who keeps trying to convince himself he's motivated by nobler things than vanity and wounded pride. If Garfield's Peter Parker is already Spider-Man before he gets his powers, Ifans' Connors is already on his way to becoming the Lizard in that he sees himself as repulsive and something less than human.

Martin Sheen’s Uncle Ben doesn’t seem to be a man keeping secrets, only a man trying not to show how he’s weighed down by longstanding regrets and probably unjustified guilt and self-recrimination. Sheen has built his characterization of Uncle Ben around the idea of Peter’s budding greatness. Ben, even more than Gwen, senses the hero within Peter, and as proud as it makes him, it also scares him. He knows that with great power---by which he means talent, brains, and the ambition to put them to work, the webslinging and the wallcrawling haven’t started yet, and when they do, he won’t know about it---comes more than great responsibility. It comes with the potential for all kinds of trouble and heartbreak that he wants protect Peter from but knows he can’t. This worries and saddens him but it also makes him feel like something a failure. He believes Peter deserves a surrogate father up to the job of helping a hero. He’s at a loss. It’s a little more complicated than the sense of loss all parents of teenagers on the brink of outgrowing their ability to protect them feel, but he deals with it in a familiar way, by being inconsistent in his approach, alternating between indulgence, humor, over-asserting his authority, and just plain asking the child he wants to help for advice on how to help him. This Uncle Ben never says the iconic line but in the two speeches that boil down to “With great power…” there’s more than a hint of apology. He feels judged by Peter, one of the few ways in which he underestimates his nephew.

Of course the movie depends on Andrew Garfield making Peter the hero Uncle Ben and Gwen expect him to be while still making him the awkward, angst-ridden, insecure, self-absorbed typical teenager he can’t help being. Garfield works this balancing act just fine. He overdoes the mumbling, mopey act sometimes, and seems a little too taken with this as one of Peter’s charms. But he is charming. As for how he compares to Tobey Maguire, it’s not a matter if he’s as good, it matters that he’s different. And he is. He’s more inward, to start. More of a jerk. Even when he’s doing good, his cockiness crosses the line into jerkiness. Which is in keeping with the idea that this Peter needs to learn more personal lessons than Maguire’s Peter did. He’s more romantic than Maguire, and sexier. Maguire’s Peter needed to be Spider-Man in order to approach Mary Jane. Garfield’s Peter lacks for poise but not confidence and Gwen and he are well on their way to hooking up before he gets bitten. And he’s smarter. Maguire’s Peter was no dope. But Garfield’s is undoubtedly a genius.

Garfield doesn’t seem to be having as much fun as Maguire did. Some of that is due to what I was trying to get at above, his Peter isn’t allowed to have much fun. That could change in the next movie, but I wouldn’t count on it.

The producers have made it plain they’re doing a trilogy. The movies are going to tell one complete story and, given that the heroine is Gwen, fans already know where that’s going.

The Amazing Spider-Man, directed by Marc Webb, screenplay by James Vanderbilt, Alvin Sargent, and Steve Kloves. Starring Andrew Garfield, Emma Stone, Martin Sheen, Sally Field, Denis Leary, and Rhys Ifans. Rated PG-13. Now available on DVD and to watch instantly

at Amazon.

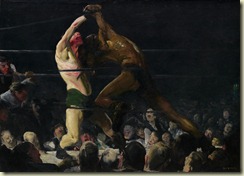

The Longest Fight

The Longest Fight