Ever hear of a fighter name of Gans?

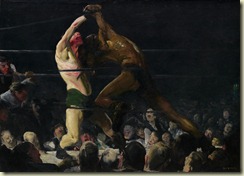

Both Members of This Club painted by George Bellows. “Joe never threw a punch unless he was sure it would land on a vital spot,” Harry Lenny, a frequent sparring partner said. “He had the spots picked out, mentally marked in big red circles on his opponent’s body: the temple, the point of the chin, the bridge of the nose, the liver, the spleen, the solar plexus. He’d pick out on or tow of these points and maneuver his opponent until he left a clear opening. It was a thing of beauty to watch Joe in the ring.”---From The Longest Fight: In the Ring With Joe Gans, Boxing’s First African American Champion by William Gildea.

Joe Gans. Never heard of him. Fighter. African American. Champ, around the turn of the last century. First black champion. First African American sports superstar.

I thought that was Jack Johnson.

Fought a big fight in the Nevada desert. Spectators arrived by horseback. Umbrellas held over the fighters in their corners.

Thought that was Jack Johnson too. His championship fight against Jim Jeffries.

It was Johnson. But it was Gans too. A few years before.

Gans did it all a few years before Johnson.

Native of Baltimore. Born 1874. Between 1891 and 1910, twenty-one years, fought close to 200 fights, won 145 of them, 100 by knockouts. Of the ones he didn’t win only 12 were losses, the rest were draws or no contests. Lightweight champ on and off, mostly on, from 1900 to 1908. His most memorable fight a forty-two round defense of his title against a holy terror named Battling Nelson in the desert outside Goldfield, Nevada, Nevada being one of the few states where prize-fighting was legal at the time. You read right. Forty-two rounds. In the desert. In summer. The Old Master. In his day considered one of the best fighters of all time. To this day, considered the best lightweight of all time. Over a hundred years of champs, contenders, pugs, mugs, and palookas have come and gone and Gans is still said to be the best.

I must have heard of him!

What I figure is, of course I’ve heard of him. He’s up there in my head, maybe not making his presence known like some other great fighters of lesser renown like Max Baer, the two Rockys, both Joe Walcotts, Gene Tunney---all heavyweights, notice. Heavyweights seem to get all the attention.---but there. Only whenever I think back on his era and what he did and what he meant, Jack Johnson just steps up and takes over the stage.

Gans did it first. Johnson did it bigger, broader, bolder, with more style and greater appetite and a lot less concern for what other people thought and more of a sense of himself as a celebrity and more determination to write a legend with himself as the hero-king. Johnson got his story told (fictionalized) in a Pulitzer Prize winning play and Oscar nominated movie, The Great White Hope, both starring James Earl Jones. He got a Ken Burns documentary. (Which I watched again before setting out to write this post. No mention of Gans.) Gans has his place in the Boxing Hall of Fame. He has a statue in an out of the way corner of Madison Square Garden. He has the painting above. Both Members of This Club by George Bellows. Great painting. Not the best-known of Bellows’ paintings of boxers, though. That would be Dempsey and Firpo. What else has he got to keep his memory alive and move it out of the shadow of Johnson’s legend?

This book now.

by William Gildea.

As you can guess from the title, the book centers on that fight with Nelson. And it was some fight.

Nelson charged from his corner, as he did every fight. Gans held his ground and ducked slightly as Nelson threw a big hook that swept above his head. Almost comically, as if pointing his opponent in the direction of his target, Gans tapped two lefts to Nelson’s head. He seemed to say, “I’m over here, friend,” in as civilized and introduction as a boxer could make. Then he got serious: He unleashed a hail of rights to Nelson’s face, landing punches repeatedly from a distance and close range. Nelson fell into a clinch.

Midway in the round, Gans doubled up with two rights to the jaw and a left to the face---a three-punch combination. All three punches hit hard. In the final moments of the round,the Associated Press reported that Gans “peppered Nelson’s face with triphammer rightsand lefts and kept this up until the gong rang…Gans went to his corner with a big lead. Blood flowed from Nelson’s ears.

Gans could take a pounding. Nelson could take a pounding and like it. The impression you get from Gildea’s account is you could’ve packed your glove with a horse shoe and hit Nelson in the mush and he’d have blinked, given his head a shake, and come right back at you, smiling.

And he fought dirty.

Nelson often seemed to get the worst of it. Gans was one of the hardest punchers ever. Knocked opponents down with short, compact jabs thrown straight from the shoulder. And he was fast. Not just with his fists. Fast on his feet. Fast to react. Throw a good one right at his head, think you’ve got him tagged on the chin, on the nose, in the eye, and at the last second he’d pull left, pull right, pull back, an inch or two, and your punch sailed right by. His counterpunch, though, had you reeling before you knew you’d missed. But it was no Sunday stroll for Gans either.

Nelson rallied in the ninth round, and he continued his comeback in the tenth and eleventh rounds. His rage was obvious as he flailed away. He landed four punches to Gans’ one. When one of his handlers shouted, “Stay with him don’t let him get away,” he practically overwhelmed Gans. In taking the momentum, Nelson, not surprisingly, held Gans and head-butted him. Siler, the referee, let it go. He chose not to disqualify Nelson because he wanted the crowd to get its money’s worth.

But in the twelfth round, as Nelson drove Gans to the ropes, he lost his footing and slipped to the floor. Gans towered over him. Siler stood aside. The rules did not require Gans to step aside or for Siler to rub clean Nelson’s gloves. There were no niceties in boxing, and there are still few. Gans looked down at his opponent. Nelson’s unprotected jaw invited what would have been a legal punch. Gans had plenty of room to swing, more room by far than he ever needed. Usually, he could find a space where one didn’t seem to be. Now, he could have swung any way he cared to, and driven his fist into Nelson’s mealy face.

But Gans restrained himself. Instead, in a sportsmanlike gesture, a humble act, really, he put out his right hand to help Nelson to his feet. Nelson accepted Gans,s graciousness. He took Gans’s hand.

That was typical of Gans, a good-hearted and kindly and fair-dealing man, in and out of the ring. But no dope. He didn’t expect Nelson to be grateful, and Nelson wasn’t.

Yet midway through the twelfth, Nelson extended his cranium, as A.J. Liebling would have put it. So much for graciousness. And later in the round, Nelson again lowered his head and rammed Gans’s face, bloodying his mouth. In the thirteenth round, Nelson did it again.

Detailed and gripping as it is, Gildea’s account of the fight isn’t the whole of his book. It’s the narrative thread on which, jumping backwards and forwards and laterally through time, he hangs other stories. Stories of Gans’ other important fights. Stories about other fighters he faced, fought, befriended, learned from, and taught. Stories about the business of boxing at the end of the 19th and early goings of the 20th Centuries. Stories about the characters who gathered around the rings and the training camps and in the backrooms of bars where fights were arranged and deals were cut. Stories of what it was like for a black man trying to make his way, make his reputation, make his fortune in a nation run by white men for white men, although the only privilege many white men enjoyed was the privilege to push around and despise and lord it over people of color. Even after he’d established himself as a champ, Gans had to deal with the humiliations doled out by white men determined to make him suffer for daring to be black and successful, some large and threatening---death threats were routine---some petty---Gans could have won many of his fights sooner and more decisively but his manager thought it prudent for Gans to carry opponents several rounds past their deserving so that the paying white customers didn’t feel they were paying to watch a black man humiliate a white man even a pug who, knowledgeable fans knew, shouldn’t have lasted past a round or two against a fighter as good as Gans.

But Gans was an extremely popular champ with large numbers of enthusiastic fans of all colors.

Many of his white admirers could only explain their liking for Gans by making an exception of him. He was the right kind of colored man, they told themselves, which amounted to a way of seeing him as not colored at all, as an honorary white man, and they extended their compliments in expectedly racist and condescending terms and tones, diminishing his achievements and their own boxing judgment in the process.

But many others were simply too impressed to worry about defending their prejudices. Gans was good, the best, in fact, better than any other fighter of the day, white or black, and if to see that and admit to it and enjoy it meant acknowledging that a black man could be not just the equal of any white man but the superior to many, well, that’s what it was.

It probably helped that Gans was quiet-spoken, modest---without being self-effacing, self-abasing, or apologetic for his talent and success---patient, even-tempered, decent-hearted, and forgiving or at least understanding. That manager he fired? The one who cheated him? Gans kept him as a friend. Didn’t let him touch his money again, but still, bygones were bygones with Gans. Even Battling Nelson, viciously and loudmouthedly racist, who boasted of his successes against black fighters as special achievements, came to like and admire Gans. Gans remained on such good terms with his first wife that when he was dying of tuberculosis he asked to be taken to her house so he could die there and she opened her doors to him and his second wife, the woman he had left her for.

About the only person Gildea reports as having harbored any sort of hard feelings towards Gans was Eubie Blake, the great jazz pianist who got his start at the hotel Gans opened with the money he made from the Nelson fight. Blake held a grudge against Gans for getting between him and a girl he was in love with. Even so, Blake continued to work for Gans and when Gans died, although Blake said he wasn’t going to go to the funeral, his wife didn’t have to work very hard to guilt him into going to the church.

Some of Gans’ popularity was due to his character. Some of it, though, may have been due to sports fans’ intrinsic sense of fairness.

Because he was a thinking fan's fighter and because he fought with precision and skill instead of coming on like a brawler, there was something of a David versus Goliath quality to his fights, even though he was usually the favorite, so decidedly the favorite that the smart money wasn’t on whether he would win a fight but on what round he would win it in. But it may have been the case that fans knew the real Goliath Gans was up against, the whole apparatus of a virulently racist society in which whites held all the power.

Gans went into that fight with Nelson guaranteed a cut of the $35,000 purse that was hardly chump change for 1906, but not a champ's fair share. Nelson, the challenger, got more, and Nelson and the promoter, Tex Rickard, at the beginning of his storied career as the essentially the founder of modern prizefighting, insisted on conditions for the fight that were far and away more favorable to Nelson. Gans needed the money. He didn't have a manager looking out for him, having recently fired his longtime manager who was worse with Gans’ money than Gans was himself, and Gans wasn’t exactly careful. Gans was not the first pro athlete who couldn't trust the people he needed to trust with his money and to protect his interests. But as a black man he lived and worked within a system that gave him very little leverage to protect himself against whites determined to cheat him.

But some of Gans’ ability to win over fans may have been due to the way most sports fans got to know not just him but all their heroes and favorites at the time, by reading about them.

There were pretty much only two sports with national followings in America at the time. Baseball and boxing. And both were extensively written about, because unless you lived close to a city with a major league baseball team---and there were only 7 before 1903---or in a state where prizefighting was legal---and there were only a few---you had to follow them through the newspapers and magazines. The Gans-Nelson fight was covered by reporters and writers from all over the country (Jack London was there.), witnessed and written about from every angle.

This meant that for many fans boxing, and boxers, came to life through words, and Gans was good with words. He was intelligent, witty, thoughtful, and could talk about his sport and his abilities knowledgeably and persuasively. Which meant that Gans himself had control over how people “saw” him. In a real way, he wrote himself into their heads as the man and professional he knew himself to be, over-writing their prejudices.

Of course there were cameras. There were movie cameras. The Gans-Nelson fight was filmed and shown in theaters across the country and around the world. But Jack Johnson, coming along just a few years later, entered the public’s consciousness by way of mass media that had become more visual. He had more cameras to play to and an audience that expected to see their heroes…and villains. And Johnson made sure the customers saw him.

What they saw was an undeniably black man, rich, famous, happy, having the time of his life and not caring what anybody thought about it, except to be more insistently himself to those who thought he should be someone lesser. And they hated him for it and rooted for his ruin.

The upshot is that this is another way Johnson upstaged Gans. Johnson’s story is the more dramatic and more representative story of the ongoing tragedy of the history of race in the United States.

After the epic fight in Goldfield, Gans didn’t retire from boxing but he fought less and less often, for less money and less prestige. He was aging, naturally. He was in his thirties. But there was more and worse to it. He had developed tuberculosis. He may have had the beginnings of it when he took on Nelson the first time. He definitely was feeling it when they fought for a second and then a third time. It took four years, but death caught up with him in 1910, right around the time Johnson fought his epic championship fight in the desert. Towards the end, he took a “vacation” out west where he’d hoped the clear, dry air would help restore his health. It didn’t. Realizing he was dying, Gans asked his doctor to send him back east so he could die among friends and family. At every stop along the way, the train carrying him first to Chicago, where his first wife lived, and then home to Baltimore was met by mobs of heartbroken fans there to say goodbye to their hero. Seven thousand people came to his funeral.

How could I have not heard of this guy?

Oh well.

I have now. And from a very good source and in the best way to get to know a boxer, still. By reading about him.

The Longest Fight: In the Ring With Joe Gans, Boxing’s First African American Champion by William Gildea, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Available from Amazon in hardcover and for kindle.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home